Christmas is a big deal at the Charles Dickens Museum, as Dickens is seen as the creator of Christmas as we know it. But Dickens didn’t invent Christmas. He popularised it, helping to preserve fading traditions.

This year is also special for us at the Museum as it is our centenary – 100 years since The Dickens Fellowship, who saved 48 Doughty Street (Dickens’s only surviving London residence) from demolition, opened the house as a museum. We first threw open our doors on 9 June 1925. One hundred years on, the Museum is a charity with a collection considered the world’s most comprehensive repository of Dickens-related material. With such a rich collection, we’re well placed to talk all things Dickens and Christmas.

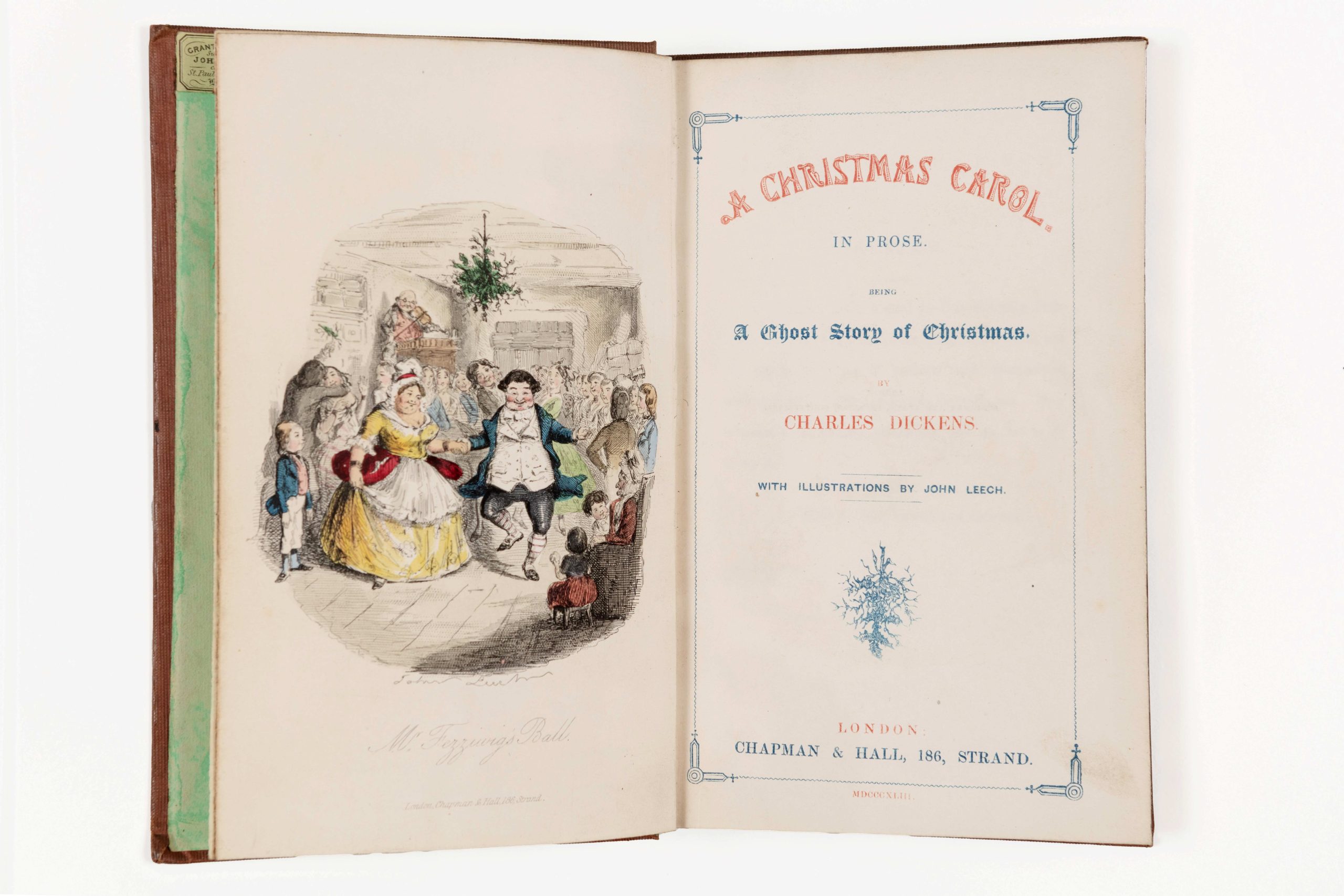

A Christmas Carol

First edition donated from the Blavatnik Honresfield Library by the Friends of the National Libraries, 2022.

Where does this myth of Dickens as the creator of Christmas come from? It’s all thanks to his most famous Christmas book, A Christmas Carol, published in 1843. It was, and still is, one of Dickens’s most successful Christmas stories. After this, he published a Christmas book every year for the next four years, as well as creating seasonal editions of his own magazines, Household Words and All the Year Round. Dickens wrote Carol in six weeks. There were 6,000 copies of the first edition, which sold out in six days (it was published on 19 December 1843 and was sold out by Christmas Eve). Demand was so high it was reprinted six times over the next six months. This little salmon-brown book captured the nation’s hearts and embedded Christmas traditions that continue today.

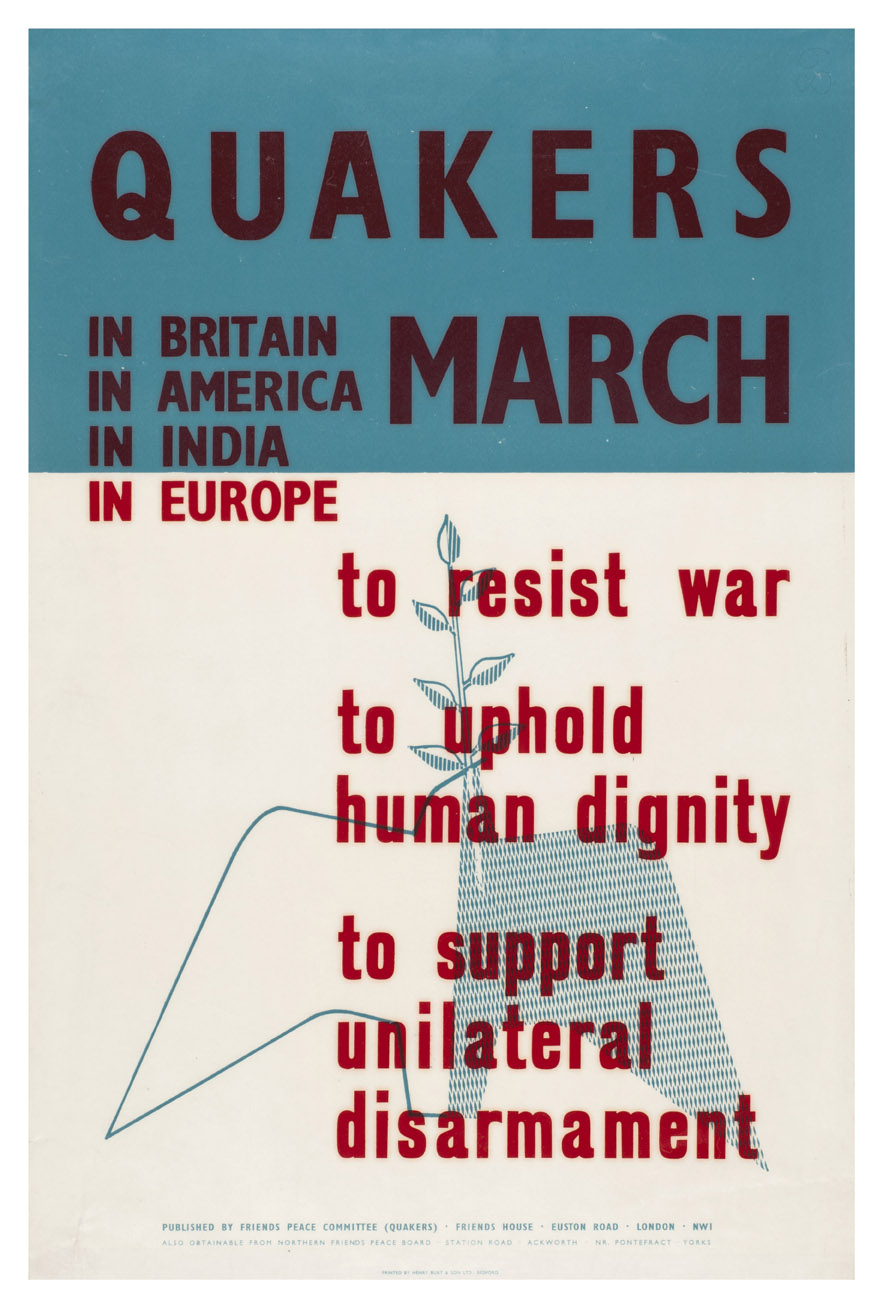

Charity at Christmas

One of these traditions is charity at Christmas. It’s been a long-standing part of the Christmas season – there were widespread traditions of gift-giving on St Stephen’s Day, which we now know as Boxing Day (26th of December). It is thought the alms box placed in the parish church to collect donations for the poor influenced the name. This evolved into giving gifts in boxes to servants. However, Dickens was keen for Christmas to return to its roots, encouraging people to act with kindness and good will at this time.

The legal background – Poor Laws

He was heavily influenced by the introduction of the Poor Laws in 1834, which created the infamous workhouses. He was also influenced by a copy of the report from the Royal Commission of Inquiry into Children Employment, which a friend sent to him in March 1843. Dickens was upset by the 1834 Poor Laws plunging children into poverty and by child labour laws keeping them there. He initially thought of writing a pamphlet to the government, but he quickly realised a novel would have more impact and A Christmas Carol was born.

The tight-fisted Ebenezer Scrooge who, through a series of ghostly visitors who show him the error of his ways, learns to understand the importance of charity and compassion to those less fortunate during the Christmas season. At the end of the novel, he visits his employee Bob Cratchit and family, buying them a huge turkey for their Christmas dinner. This act of charity ultimately saves their son Tiny Tim, whose health was affected by the family’s poverty. The characters of Scrooge, Cratchit and Tiny Tim have entered the public consciousness and speak to the values of kindness, compassion and good will to all.

This autographed quote is of Tiny Tim’s famous line: ‘God bless us, every one’ and is signed by Dickens. It’s likely he gave it to an audience member after a public reading of A Christmas Carol in Aberdeen in 1858.

Dinner traditions

But did Dickens like Christmas? You’ll be glad to hear he did. The Dickenses were feasting and frolicking like everyone else. His eldest daughter Mary, known as Mamie, remembers when they were small, Dickens took the children to a toy shop in Holborn to choose a gift. There were home theatricals, especially on Twelfth Night which marked the end of the Christmas season and their eldest son Charley’s birthday. The family threw a huge party and Dickens would do magic shows. Also, like most middle-class Victorian families, turkey would be the centrepiece of the Christmas table and the Dickenses were often gifted one. Dickens wrote this letter thanking his printers, Bradbury and Evans, for the turkey they sent. On the 2nd of January he wrote:

‘I determined not to thank you for the Turkey until it was quite gone, in order that you might have a becoming idea of its astonishing capabilities. The last remnant of that blessed bird made its appearance at breakfast yesterday — I repeat it, yesterday — the other portions having furnished forth seven grills, one boil, and a cold lunch or two.’

A festive museum

If you’re in London over Christmas, be sure to visit the Charles Dickens Museum while we’re all decorated for Christmas to see for yourself how the Dickenses celebrated the festive season. Also, keep an eye on our website for Christmassy and future events at www.dickensmuseum.com.

Further information

Written by Kirsty Parsons, Curator at the Charles Dickens Museum.

Edited by Isabel Lauterjung, Blog Coordinator with Explore Your Archives.

Browse the museum’s holdings online: Collections Online | Charles Dickens Museum.