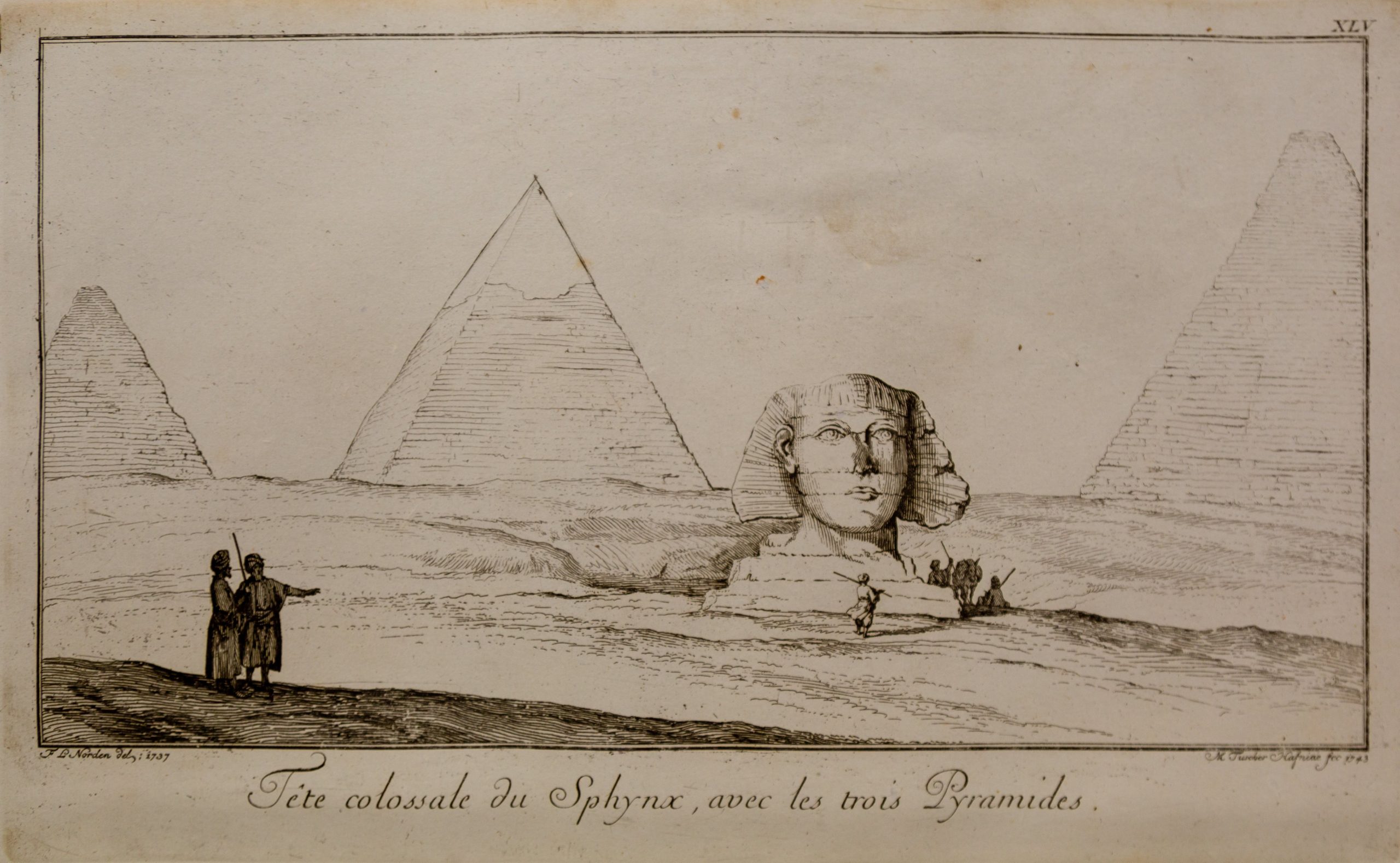

This month at EYA we are celebrating #Travel. Ruth Gooding, Special Collections Librarian at the University of Wales Trinity Saint David gives insight into the travel account and illustrations produced by Frederik Ludvig Norden in his book Travels in Egypt and Nubia (1757).

Frederik Ludvig Norden was a Danish naval officer, as well as the author of the first comprehensive guidebook of Egypt. He had joined a Danish expedition, aiming to establish commercial relations with ‘the Emperor of Ethiopia’ and ‘with the design of enriching the learned world.’ Norden, a talented cartographer, was the official representative of Christian VI.

© Special Collections and Archives, UWTSD.

The party set sail from Livorno in Tuscany in summer 1737, landing at Alexandria after a month’s voyage. Norden was fascinated by the obelisks there, as well as by the two columns, “Pompey’s Column” and “Cleopatra’s needles.” The group then travelled to Cairo by camel; Norden’s ill health forced them to stay there for four months. Still, he was able to see everything in the area, including visiting the pyramids and even entering the Great Pyramid.

© Special Collections and Archives, UWTSD.

Voyage up the Nile

That autumn the group voyaged up the Nile. People still sailed in the same way as the ancient Egyptians; a man at the prow with a long sounding pole measured the depth of water. As they travelled further south, the party had more and more trouble with robbers, onshore as well as on the river. Predictably enough, too, the Egyptians wanted baksheesh (a gift or tip) to let the Europeans see them. Possibly more happily, Norden noticed his first crocodile, north of Asyût, midway between Cairo and Aswān.

The party reached Karnak and Luxor on 11 December. Afraid of the hostile local population, the skipper was reluctant to let his passengers go onshore. Still Norden was able to visit Thebes, an ancient capital of Egypt. The party arrived at Aswān, at the First Cataract of the Nile, a week later. At Kalâbasha, the frontier between Egypt and Nubia, the local people commanded the ship to land so the Europeans ‘could distribute their riches.’ Sailing further south was difficult, as the river was narrow and full of whirlpools.

© Special Collections and Archives, UWTSD.

The return journey

Although the group had hoped to reach the Second Cataract in Nubia, the boat captain refused to sail further south than Derr, 150 km short of their target. On the return journey, Norden did visit the temples at Luxor, Gurna and Karnak, then half buried in sand. At Luxor, he measured most of the ruins for three hours after midnight, checking his work at dawn.

The party got back to Cairo in February 1738, after a round trip of 2000 kilometers. They stayed in Egypt for another four months; Norden took the opportunity to revisit the pyramids. Everywhere he went, Norden had made plans, drawn views and noted the dimensions of the monuments. Alongside this, he had taken careful records of hieroglyphic texts. He had also kept a diary and a notebook, recording his impressions of the towns and villages he visited.

Back home in Denmark

Back in Denmark, Christian VI asked Norden to prepare his manuscripts and drawings for publication. He had produced more than 200 drawings and sketches, 29 detailed maps of the Nile and 2 survey maps. Norden translated his notes into French, the international language of the Enlightenment. Sadly though, his health was failing; he died of tuberculosis in September 1742, aged only thirty-four.

Norden’s plan of Thebes (left) and Norden’s map of the first part of the journey down the Nile (right). © Special Collections and Archives, UWTSD.

Travels in Egypt and Nubia

All his drawings and notes were passed to the Danish navy; his book Voyage d’Égypte et de Nubie was finally published in 1755. Norden’s maps and drawings were engraved by his friend, Marcus Tuscher. The English edition, Travels in Egypt and Nubia, was translated by Peter Templeman and published by the Royal Society in 1757.

Norden was modest about his achievements, writing to the members of the Royal Society, ‘I lay claim myself to no erudition, and desire you will only look upon what I say, as the report of a faithful traveller …’

As well as recounting his own adventures, he described the land of Egypt, including its ancient monuments, history, natural history and present-day customs.

© Special Collections and Archives, UWTSD.

The pyramids

For Giza, he was the earliest person to make detailed plans of the pyramids. He was careful to avoid speculation, writing, ‘All that can be advanced as certain, is, that their fabrick is of the remotest antiquity …’ Still, he conjectured that their construction preceded the development of hieroglyphics. After his detailed description of the pyramids, he went on to offer some advice to fellow travellers.

‘When you are got to the entrance of the first pyramid, you discharge some pistols, to fright away the bats … After these necessary preliminaries, you must have the precaution to strip yourself entirely, and undress even to your shirt, on account of the excessive heat, that there constantly is in the pyramids.’

© Special Collections and Archives, UWTSD.

His work provided Europe with details of the ancient monuments sixty years before Napoleon’s campaign. In particular, his drawing of the Great Sphinx showed that its nose was already broken; the damage could not have been the work of French troops.

UWTSD’s copy of Travels in Egypt and Nubia was donated by the East India Company surgeon, global traveller and slave owner Thomas Phillips, in 1845.

Written by Ruth Gooding, Special Collections Librarian

Coordinated by Anya Hopkins, Explore Your Archive Blog Coordinator