From coded whispers about daily tasks to private reflections, come and unravel Anne Lister’s coded musings beyond romantic aspects. This month we welcome the West Yorkshire Archive Service for an EYA blog edition on secret histories.

Anne Lister: the incredible Yorkshire woman, whose journals tell the tale of a landowner, traveller, businesswoman and, of course, lesbian. Her prolific journals span 26 volumes, composed of two small notebooks and 24 hardbound volumes. These contain over five million words- with around 1/6th of these written in a secret code she devised to write of her relationships with women.

The telling of these relationships brought Anne Lister ‘out of the closet’ (or in this case, from behind the wall panels in which the journals were hidden) most notably through the works of Helena Whitbread, and in the BBC drama “Gentleman Jack” by Sally Wainwright. Particular mention also needs to be made of the works of Jill Liddington, Muriel Green and Phyliss Ramsden.

After Anne’s death in 1840, her journals lay dormant, until discovered decades later by her ancestor John Lister, the Hall’s final Lister resident. Along with his friend, Arthur Burrell, John set out to read them, but first, they had to break her secret code. Using a scrap of paper on which Anne had written ‘In God is my hope’, with the word ‘hope’ written in code, they deciphered Anne’s secret language and thus revealed the intimate parts of her life she wished to be hidden.

Fearing the consequences of such a scandal getting out, the pair considered burning the diaries. However, John recognized the journals’ historical value and couldn’t bring himself to do so. Instead, he placed the diaries behind one of the panels in Shibden Hall, where they remained until 1933 when John passed away. Subsequently, the Hall and its hidden treasures fell into the hands of Halifax Corporation (now Calderdale Council).

The Genesis of the Code

Anne devised the code during her time at school in York, as a means to communicate with her then-girlfriend, and first love, Eliza Raine. This substitution cipher, devoid of word breaks and punctuation, merged Greek and algebraic symbols. The entries captured their youthful turmoil in notes strewn with 19th-century teenage angst, where they endearingly addressed one another as husband and wife.

Later throughout her life, this code provided a means of recording her love, pain, and sexual experiences with other women. Some were unrequited, some successful, some incredibly graphic, but all were safeguarded within her journal’s pages.

Beyond the ‘romantic’

Anne’s cipher chronicled more than just her love life. It also captured the banality of daily existence— mending garments, tallying coins, and other seemingly trivial details. This raises the question: why cloak such ordinary matters in secrecy? Anne’s selections for coded entries reveal her vulnerabilities, the ordinariness of life, and a journey of self-discovery.

Her journal served as a confidant in much the same way as friends do today. Though we are often reluctant to admit it, not all gossip is benign. Anne’s coded musings were akin to whispered private remarks—perhaps an unflattering personal observation, or a wry joke at someone else’s expense.

Some of the coded passages are understandable in their desire for secrecy. When you read her descriptions of self-medicating for a venereal disease, making observations of boils, and documenting bowel movements, it’s not surprising that Anne wished to keep these matters private. Similarly, her less-than-flattering reflections on contemporaries align with a desire for discretion. One need only look to nearby Wakefield and the fate of the diaries of fellow Yorkshire woman Clara Clarkson. After Clarkson’s death, esteemed individuals in neighbouring Wakefield petitioned to destroy her diaries, fearing the possibility of scandal if the pages were to come to light.

She also used the code to discuss matters and family links, that she felt beneath her. Anne held herself to a high standard and aspired to a higher position in society. She was after all a land owner, determined to make her Shibden estate profitable and her home Shibden Hall as grand as (her wife’s!) finances would allow. She sought the company of high society and aimed to distance herself as much as possible from her family’s ‘trade’ roots. Her disapproval of her sister’s declared intention to marry a local successful tradesman, John Abbott demonstrates this most vehemently.

Ultimately the code, and the journal as a whole, provided Anne with a release. This gave her the mental freedom to authentically express herself in all aspects of life and love. She writes in May 1824 “What a comfort is this journal. I tell myself to myself and throw the burden on my book and feel relieved”.

Where to read more

You can view Anne’s journals on the WYAS catalogue. Transcriptions are available up to 1834 (at the time of writing). The remaining transcripts are due to be released throughout 2024.

Written by Jenny Wood: Anne Lister Diary Transcription Project Lead, West Yorkshire Archive Service

Socials:

- Learning Through Play: Froebel’s Educational Philosophy and the Power of Play

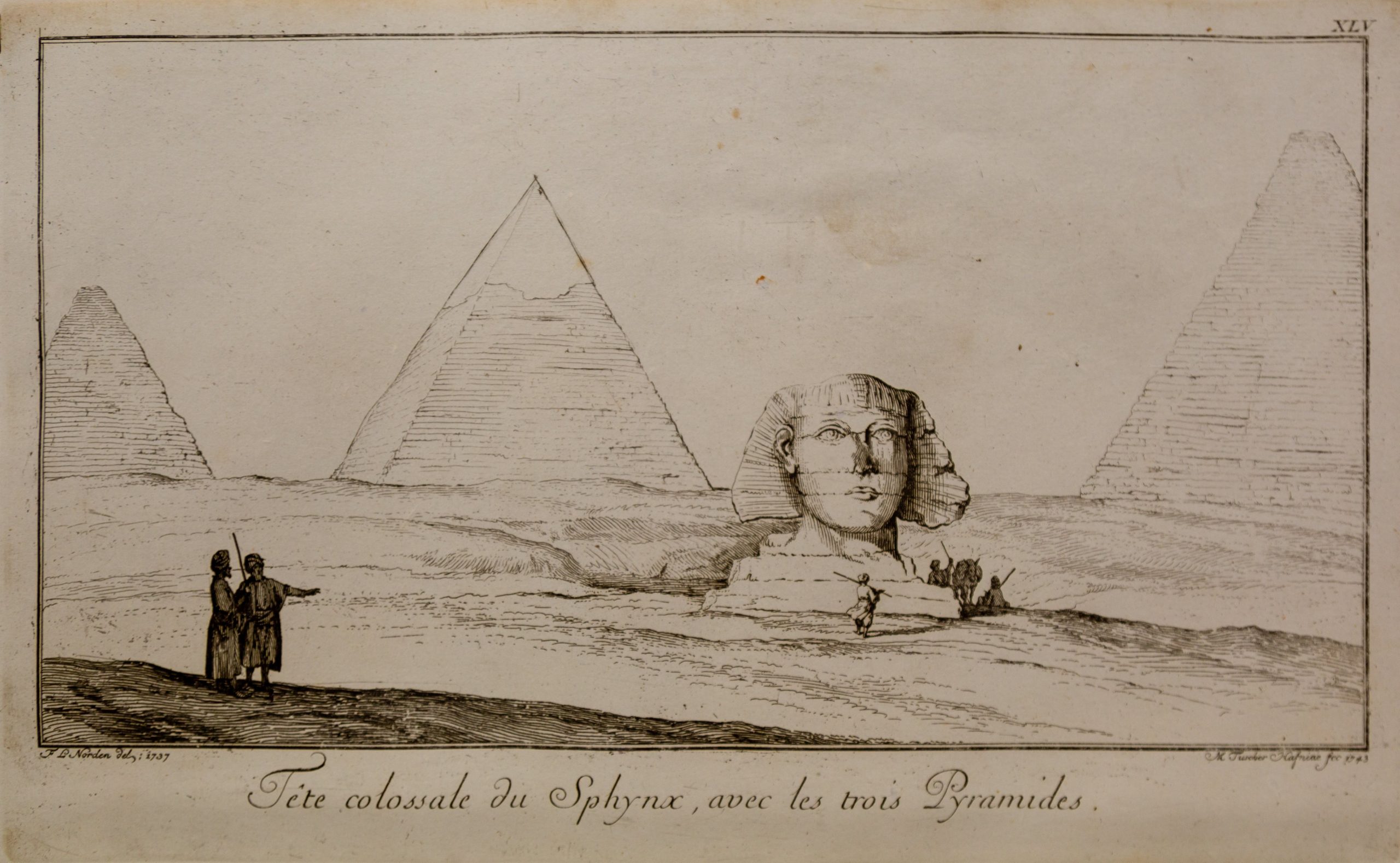

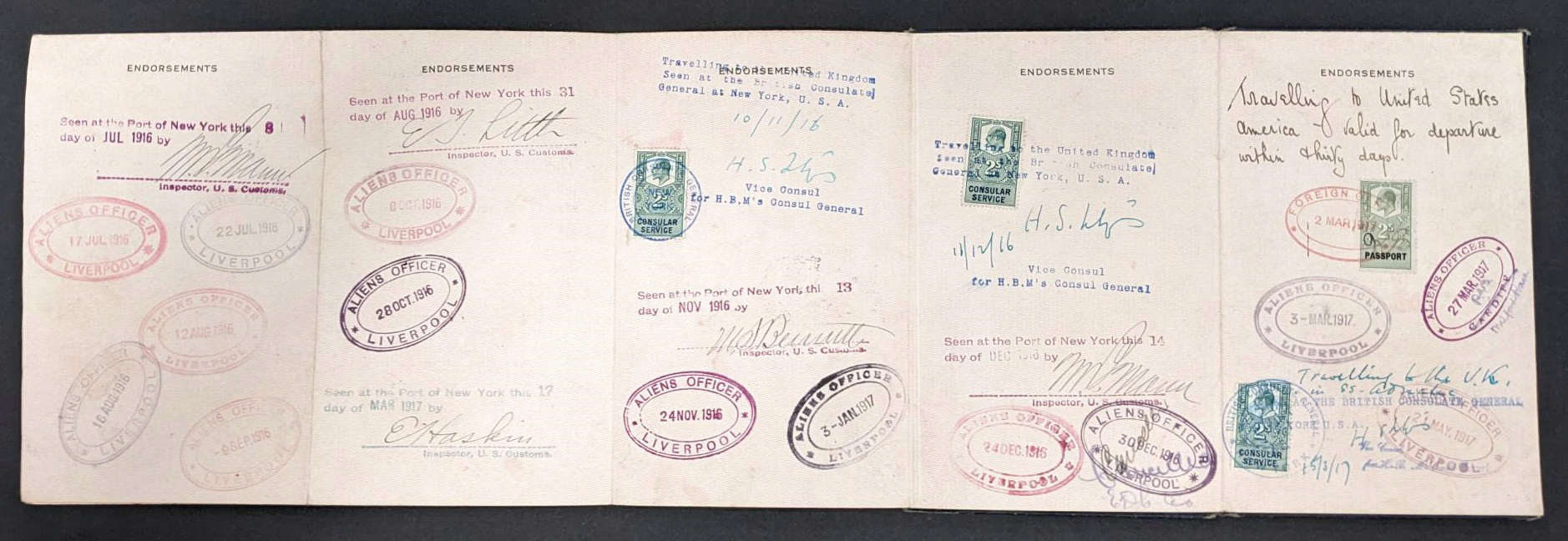

- Putting Egypt on the map: Frederik Ludvig Norden’s Travels in Egypt and Nubia

- Exploring the Atlantic with Frank White

- Photographic Collections at the National Fairground and Circus Archive

- Grace McIntosh: The Life of a Victorian Criminal

Animals archive Archives art British Business Archives christmas collections diaries diary Digital Collections Diversity Diversity Allies education explore EYA fauna flora gender heritage History Inclusion Ireland letters library Local local history Local History and Community london museum Nature photography posters queer records school science Scotland social student theatre Twitter university Women WWII