Back in October for our Halloween-themed post, we spoke to the University of Glasgow Archives & Special Collections about the role the Ferguson Collection plays in increasing our understanding, and the Victorian conception of, the supernatural and the occult. What follows is part two. This time we delve into the murky waters of belief and disbelief, as we examine in further detail a world of scientific experimentation into the supernatural and questions of what makes an “eerie” tale.

3. (Sp Coll Ferguson Ao-y.27) Real Ghost Stories

Above: Cover of Ghost Stories. With permission of University of Glasgow Archives & Special Collections [please cite reference number]. Ed. W. T. Stead, London: (1891).

A cautionary note

To begin with, Real Ghost Stories: A Record of Authentic Apparitions contains allegedly true tales of supernatural or ghostly events. Indeed, these events were related by members of the public to its editor W.T. Stead.

Real Ghost Stories begins, in a typically moralising Victorian tone, with a cautionary note that it should not be read by “any one of tender years, of morbid excitability, or of excessively nervous temperament”. The preface by W.T Stead explains why he has devoted this edition of the magazine to the subject matter of ghosts. Indeed, it outlines his belief in the need for a scientific approach to be used in researching supernatural phenomena.

Above: Detail from cautionary note. With permission of University of Glasgow Archives & Special Collections [please cite reference number].

A case for the supernatural

Part One of the volume, entitled ‘The Ghost that Dwells in Each of Us,’ discusses dual or multiple personalities or ‘submerged souls’. Additionally, it details some cases of this type investigated by the Society for Psychical Research. Meanwhile, part Two deals with ‘The Census of Hallucinations’.

In October 1891, Stead wrote to Frederick W. H. Myers, the Hon. Secretary of the Society for Psychical Research. This is what he said:

“The publication of Real Ghost Stories will, I hope finally dispel the absurd and unscientific prejudice which has hitherto rendered it almost impossible to persuade ordinary people to admit that they have seen or heard anything of the kind which it is popularly described as ‘supernatural'”.

w.t. stead to frederick w.h. myers, october 1891

Deny Everything … or not?

The stories (or cases) in this volume cover such subjects as clairvoyance, premonitions, ghosts, poltergeists, second sight, and spiritualist séances. In fact, they comprise Stead’s attempt to take his own Census of Hallucinations. But not on a scientific basis, but by just recording tales related to him, in person and by his readers.

For instance, in Chapter IX, there is a typical story of a man Stead met at a dinner held by the City Liberal Club in Glasgow. David Dick, a 35-year-old auctioneer, told Stead that he did not believe in ghosts but that, nevertheless, he had seen one. He related that he had left his office in Sauchiehall Street one afternoon at half past three in the afternoon. Following this, he entered Renfield Street where the ghost of his father joined him. However, there was one problem. His father had been dead six years. They walked along Renfield Street talking as if the ghost were an ordinary person. At the corner of St. Vincent Street, the ghost vanished. Mr Dick was not at all alarmed by his encounter with the apparition. In fact, he thought it seemed perfectly natural at the time.

A chilling visitation

By comparison, Stead makes much of the fact that Mr. Dick had not experienced anything of a similar nature and records him as saying “As I said, I do not believe in ghosts; all I know is that I did walk down Renfield Street with my father six years after his death”. Most of the cases are similar tales of ordinary people with extraordinary experiences to relate. The image of the ‘crayon drawing of a spirit face’ was drawn by a Mr Charles Lillie on the morning after he had attended a private séance at a house in Bayswater. He, and four others, all claimed to have seen this apparition during the séance. How chilling!

Above: 1) Mr Dickinson (Detail from page 54); 2) View of Renfield St (Detail from page 88); 3) Crayon drawing of spirit face (Detail from page 79). With permission of University of Glasgow Archives & Special Collections [please cite reference number].

This review is from our Book of the Month archive. Read more here: https://www.gla.ac.uk/myglasgow/library/files/special/exhibns/month/dec2007.html

4. (Sp Coll Ferguson Ak-d.69) The Eerie Book

Above: Cover of The Eerie Book. Ed. Margaret Armour, London: 1898. With permission of University of Glasgow Archives & Special Collections [please cite reference number].

The Eerie Book could certainly be considered a compendium of Gothic Horror at its finest. The collection of sixteen tales of the macabre and supernatural features authors such as Edgar Allen Poe, Hans Christian Anderson, and George W. M. Reynolds. Produced in 1898 by Scottish novelist, poet and translator Margaret Armour, this anthology sits apart from the other tomes in her repertoire, which consists mainly of prose and translated works.

A compendium of classic 19th c writers – Mary Shelley and Edgar Allan Poe

Armour’s The Eerie Book boasts two mid-century tales by Edgar Allan Poe, the master of American Gothic, ‘The Masque of the Red Death’ and ‘The Cask of Amontillado’. Also featured is George W. M. Reynolds’ ‘The Iron Coffin’, extracted from his novel Faust. Although his work is rarely come across nowadays, Reynolds was a prolific writer and hugely popular in the mid-Victorian period, especially among the working classes. The compendium also includes an abbreviated version of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, and chilling tales by Scottish author Catherine Crowe.

Above: Title and contents page of The Eerie Book. With permission of University of Glasgow Archives & Special Collections [please cite reference number].

Folklore, the Gothic, sensational fiction and ghosts

Even so, Sarah Gillies (né Bissell) discussed this particular work in 2015 in a feature for the University of Glasgow Library blog. She writes, “this collection, edited by Margaret Armour and illustrated by her husband William Brown MacDougall, offers a plethora of evocative tales from both sides of the Atlantic. While the reader may already be familiar with some of the chosen works, there are one or two relatively unknown treasures. The collection does not focus exclusively on ghosts, but also encompasses folklore, the Gothic, and sensational fiction. The stylised illustrations by Glaswegian illustrator MacDougall provide effective companions to these works. MacDougall contributed artworks to the infamous fin de siecle journal, The Yellow Book, and, alongside his wife, collaborated with its art editor Aubrey Beardsley on various projects. There are certainly echoes of this aesthetic journal in the strange, Art Nouveau illustrations that appear throughout this collection.”

The Eerie Book or “The Cheery Book”?

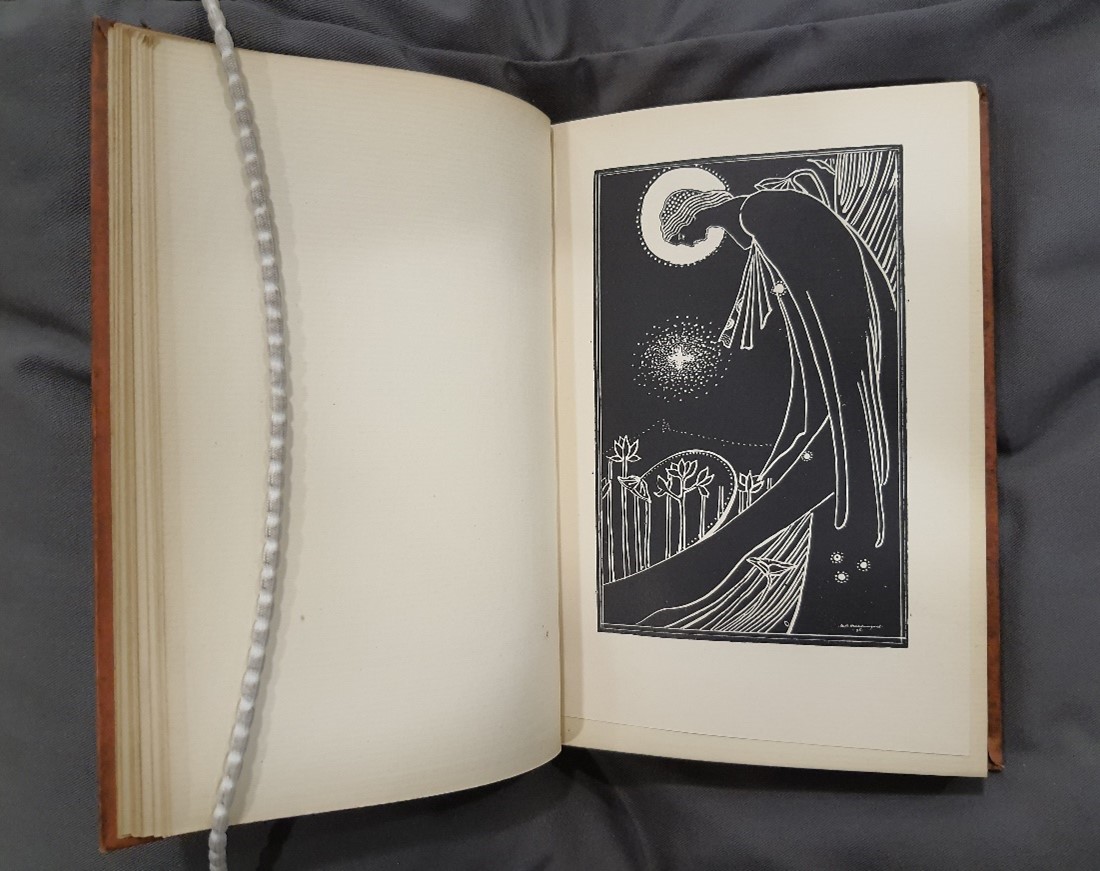

As Gillies suggests, the artwork for The Eerie Book is as significant as the text. Arguably, the collaboration between Armour’s chosen texts and MacDougall’s somber and allegorical illustrations produces a harmonious and stylish “blend of ghostliness and aestheticism.” For this reason, the front cover, bound in red cloth, features a barefooted and caped ‘witch,’ and is drawn in Macdougall’s synonymous Art Nouveau style; as are the other fifteen full-page illustrations throughout the book.

Above: Three of MacDougall’s full-size plates from The Eerie Book. With permission of University of Glasgow Archives & Special Collections [please cite reference number].

“Of course, tastes in literature vary so greatly that not everyone will appreciate this book,” Gillies writes. Ferguson, who appeared to have acquired his copy of The Eerie Book in 1908, added his own personal annotations to the book, as he did with others in his collection, disclosing his frank and honest opinion. It seems that, despite the celebrated works it contains, the eeriness in the tales and illustrations appeared to be somewhat lacking for Ferguson. His note reads:

“The pictures are not eerie. They are only wretched productions under the corrupt influence of Aubrey Beardsley. The stories are not in the least eerie. The only two that claim any merit at all are those of Savile. It is difficult to see what was aimed at in printing the book at all.”

an annotation from the copy of john ferguson

Alas, at least what can be said is that Ferguson inevitably decided to keep The Eerie Book amongst his collection, despite his despondence with the publication, and subsequently we have gained the opportunity to see and preserve a truly unique contribution to Gothic Horror, Victorian, and Scottish publishing history.

Read Sarah Gillies’ blog for further information on The Eerie Book: https://universityofglasgowlibrary.wordpress.com/2015/12/11/ghost-stories-for-christmas/

Written by Erin Veitch of the University of Glasgow Archives & Special Collections

Edited by Jake Doyle, Blog Coordinator for Explore Your Archive, MLitt Archives and Records Management Student and Archive Assistant at Suffolk Archives

Further information

Website: https://www.gla.ac.uk/myglasgow/archivespecialcollections/

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/uofglasgowasc/?hl=en