The Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland (RAS) was established in 1823 as an independent organisation. It was set to promote research and public interest in the histories and cultures of Asia. Many of its founders had been members of the Asiatic Society of Bengal. The latter was founded in 1784 by the famous linguist Sir William Jones.

Why was the Royal Asiatic Society founded?

In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, greater numbers of Europeans moved to Asia. They lived and work in different parts of Asia as diplomats, merchants, and soldiers. Trade increased and the British Empire rapidly expanded. But there was still very limited understanding of Asian cultures in Britain, or elsewhere in Europe.

The RAS sought to improve public knowledge about Asia. It sought to include supporting translations of classic works of literature. It tired to make it easier for scholars to access books, art, manuscripts, and other objects relating to Asian cultures.

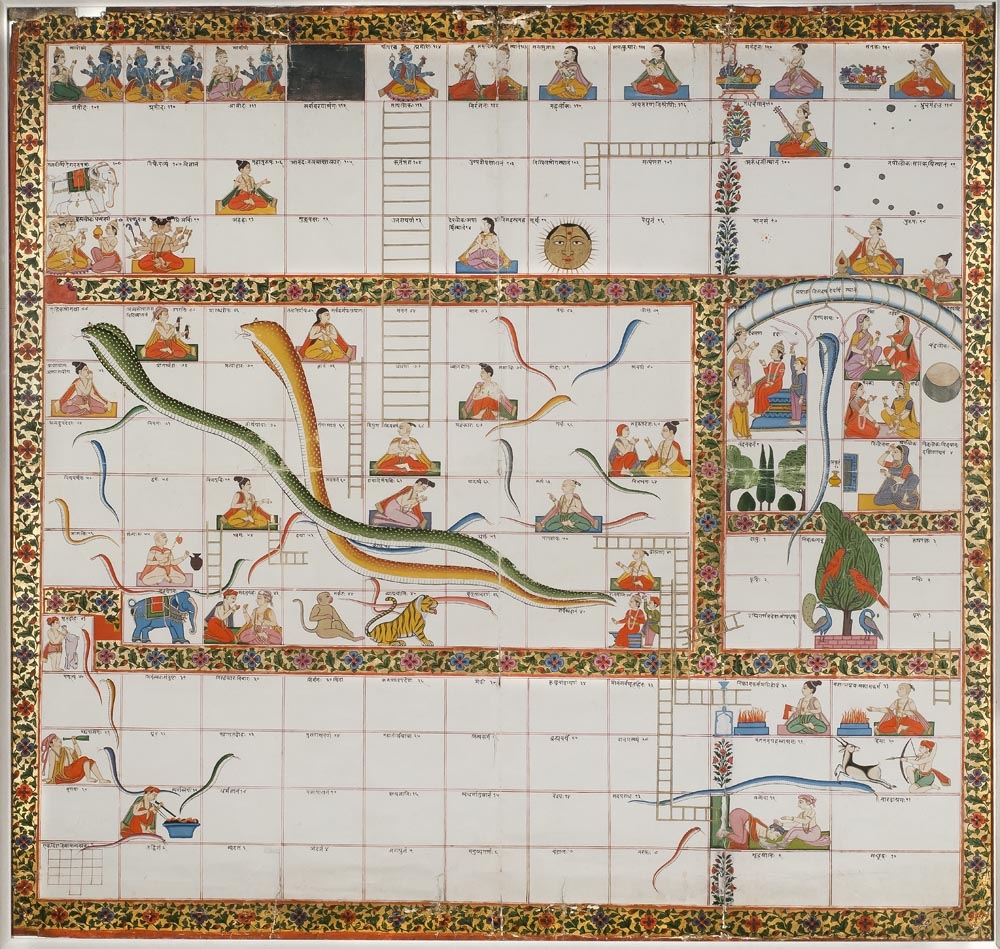

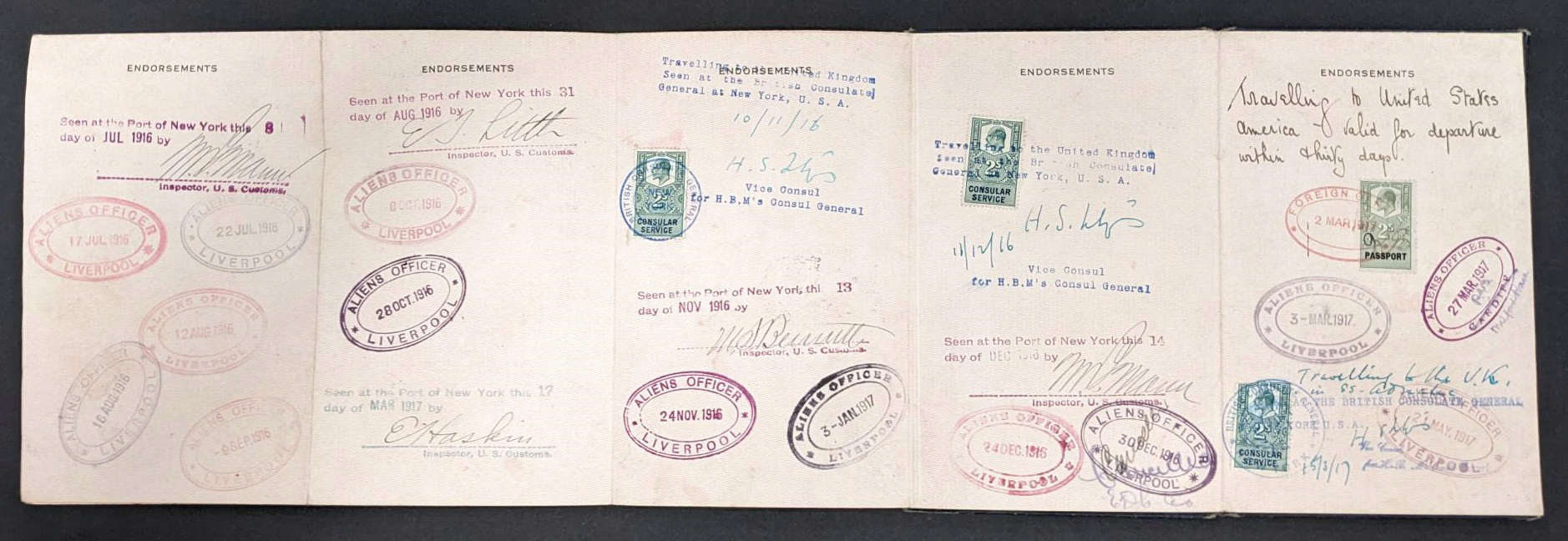

The Society’s members often donated their own collections to aid this purpose. From Persian manuscripts to Indian paintings to Japanese ukiyo-e theatrical prints, most of these are still with us today. They form the core of the Society’s holdings.

Today, the Royal Asiatic Society is a charity

The Society provides free public access to all its collections via the Reading Room service. We also keep looking for new opportunities to make cultural history available to as many people as possible.

We want people to know what we have, and we also want people to know the stories behind the collections.

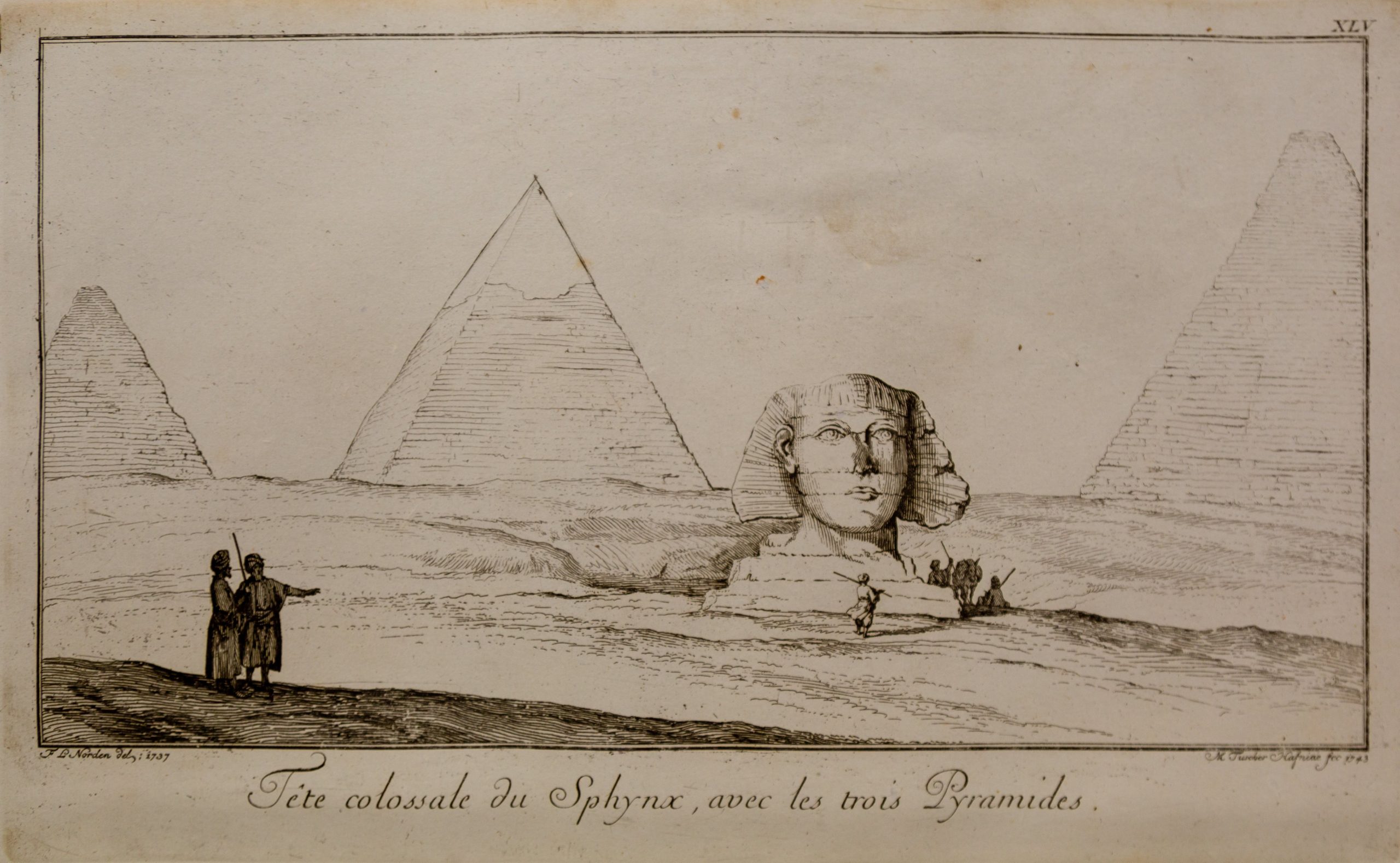

In addition to promoting new study of Asian cultures, we want people to know how British people in the past have studied Asia. Many British people who spent time in India, China, Persia or elsewhere collected art, manuscripts and other objects. To better understand local histories and cultures, or from simple aesthetic or intellectual interest.

Today, there is wide public awareness that some cultural artefacts were acquired by Europeans in Asia during or after military conflict. But private scholarly collections, many of which were later donated to libraries and museums, often entered European hands legitimately. For example typically purchased on the market, or acquired as copies, commissioned by European enthusiasts, of original paintings and manuscripts.

The accessibility of the collection

Digital technology is a great way to make collections accessible to people. People who live outside London and who might have found it difficult to access our collections. Online access is particularly relevant to the Society because many of our collections originate from Asian countries. Our collections may contain much of interest to people who live thousands of miles away. Thanks to digitisation, it’s much easier for people living in Nepal, Malaysia, or anywhere else to see what we have.

Although only a portion of our collection is digitised, this amount has grown dramatically in recent years. We have now put hundreds of manuscripts, paintings, and early photographs online. The archive of Thomas Manning is also online. He was one of the first Englishmen to study Chinese and a close friend of the Romantic author Charles Lamb.

The Society aspires to digitise and make available online as much of our collection as possible. In recent years we have been grateful for opportunities to collaborate. We have done so with partners including the National Library Board of Singapore and the Internet Archive. Now, the Society can provide direct access to its digital collections. It is done through its Digital Library, launched in 2018 with the support from the Friends of the National Libraries.

The Covid-19 pandemic has meant our building has been closed since mid-March. We have been especially grateful that the Digital Library means people can still access some of our most important collections. We have added new digital collections to the platform and we will continue in the weeks and months ahead.

The need to share

The government lockdown has revealed how embedded digital technologies have become throughout our daily lives. So many people have remained productive while “working from home”. But the lockdown also reminds us how much of our cultural heritage is now available to see online, from home, while libraries, archives, and museums are shut. Of course, what is online is still only a fraction of our country’s rich heritage collections. Staff and users alike are keen to see heritage institutions safely re-open, so that our cultural life can begin to return to normal.

But, thanks to digital technology, the past decade has seen a dramatic change in the accessibility of collections. Now, even a small institution like the Royal Asiatic Society can have its own digital collections platform.

When libraries and archives strive to deliver valuable content to their users, they look at the example of what their colleagues have achieved elsewhere. We can imitate what has worked well in other cases. We can try to avoid repeating mistakes that have been made before. In the process, while we are pursuing our own priorities and the needs of our users. We are also contributing to a process of selection, and helping good ideas to become more widespread. In this way, piecemeal innovations across different services can be unconsciously coordinated. These lead to general improvements in services across wide areas, in ways nobody can foresee. Even small libraries and archives ultimately benefit from sophisticated applications and techniques developed by people more expert than us.

Looking into the future

Heritage professionals everywhere are looking forward to re-opening. Archives, libraries, galleries, and museums are working together to solve the challenges which that involves. When we think about future goals and ambitions, we should reflect on how we have responded to challenges in the past. In doing so, we can reflect on the processes that have served us well. The ingenuity of our technically-minded colleagues, the care and diligence of archivists and curators, and the imagination and passion of creators, scholars, and collectors, have helped create the rich heritage environment we enjoy today.

By Edward Weech

Further Resources

- Contact: library@royalasiaticsociety.org

Related Posts